Red meat has been getting a lot of media attention as of late.

The typical media message is that we are all eating too much red meat and need to either cut down or replace it with poultry.

However, is red meat really dangerous?

Moreover, is there any robust and rigorous evidence that it can cause harm?

This article examines the evidence on red meat and health and tries to answer this very question.

Why Is Red Meat “Bad” For You?

According to the negative health claims, red meat can increase our risk of pancreatic, prostate, and (especially) colorectal cancer.

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) deemed red meat to be a ‘Group 2A carcinogen,’ which means that red meat is “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

Explaining their decision, the WHO state that (1);

“In the case of red meat, the classification is based on limited evidence from epidemiological studies showing positive associations between eating red meat and developing colorectal cancer as well as strong mechanistic evidence.”

For those who are unaware, epidemiological studies are observational in nature and typically based on answers to food frequency questionnaires (FFQs).

There are also epidemiological links between red meat and cardiovascular disease.

As a result of these “risks,” most health and dietary organizations recommend limiting red meat consumption.

For example, the National Health Service in the UK recommends no more than 70 grams of red meat per day. This amount equates to a recommended intake of no more than 500 grams of red meat per week.

In the United States, the American Heart Association merely advise “limit red meat,” and if you do decide to eat some, to “select the leanest cuts available” (2, 3).

Key Point: Red meat is classed as a carcinogen by the World Health Organization, and advice tells us to limit red meat – based mainly on data from epidemiological studies.

But… There Are Many Benefits of Eating Red Meat

Next, we will look at the research on red meat in greater detail to see if the epidemiological concerns are warranted.

Before that, it is worth remembering that red meat has many health benefits too.

Here is a quick rundown of the positives;

- Red meat is a source of highly bioavailable protein.

- Significant provider of B vitamins – especially vitamin B12.

- Rich in essential minerals; particularly iron, selenium and zinc (4).

- Contains various bioactive compounds that offer benefits, such as creatine, carnitine, CLA, glutathione, and taurine (5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

A Significant Source of Nutrition in the Human Diet

It is also important to note just how much nutritional value red meats like beef, lamb, and venison provide in the average human diet.

An interesting recent study analyzed the contribution of red meat to vitamin B12, iron and zinc status across five ethnic groups in the United States.

These groups included African American, Caucasian, Japanese American, Latino, and Native Hawaiian people.

Across these groups of people, red meat contributed (10);

- 19.7 – 40% of the RDA for vitamin B12.

- 11.1 – 29.5% of the RDA for iron.

Additionally, when we think about the other B vitamins and protein contribution red meat makes, it is clear that it is an abundant source of essential nutrients.

Key Point: Red meat is nutrient-dense, and it provides a range of important nutrients.

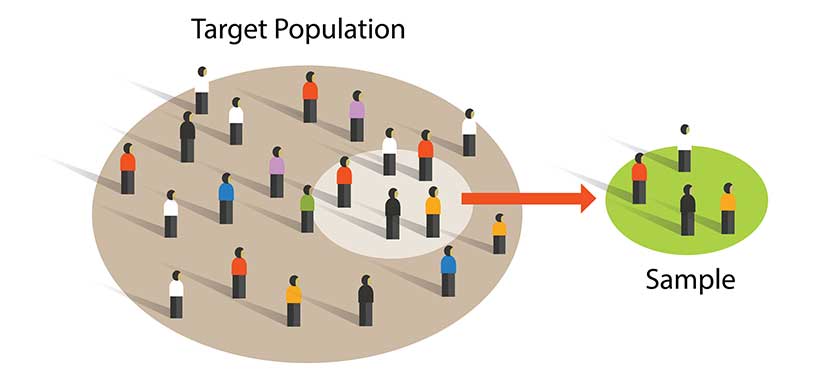

The Difference Between Observational and Randomized, Controlled Trials

Before we analyze the studies on red meat, it is essential to know the difference between observational studies (epidemiology) and randomized, controlled trials.

Pros and Cons of Epidemiology

Epidemiology can be useful to monitor health trends in population groups.

For instance, a successful use of epidemiology came in identifying the risks of smoking.

Since smoking populations tended to develop lung cancer at a much higher rate than non-smokers, we could identify the harmful link between smoking and lung cancer.

However, epidemiology can only show a correlation; it does not prove causation.

That said, when epidemiological associations are robust and consistent across varying population groups, it is highly likely to signal (yet still not prove) causation.

On the other hand, there are also some downsides to epidemiology.

The Downside of Epidemiology

Let’s use the epidemiology of red meat as an example. We know that there is a link between red meat and cancer, but what kind of red meat is that?

Does a traditional beef and vegetable stew increase cancer risk? Alternatively, is it only the red meat consumed as part of an ultra-processed meal that raises the risk?

For instance, we know that approximately 60% of total energy intake in the American diet comes from ultra-processed foods (11).

If we assume that 60% of red meat comes part of an ultra-processed meal, that means people eating more red meat are likely eating more meals like cheeseburgers and fries and beef pizzas.

In this case, is it the beef that causes problems, or the food served alongside the meat?

The answer? We do not know.

The ‘Healthy User Bias’

We should also consider a scenario known as the “healthy user bias.”

Over the past several decades, the consensus has been that red meat is “bad” for us owing to its saturated fat content.

As a result, most health-conscious people will have limited their red meat consumption.

On the other hand, the individuals who have been eating red meat (a perceived health risk) are more likely to partake in other unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking and excessive drinking.

In fact, this is something that many different studies note as a potential confounder.

Here are two such studies;

- Study: High dietary red meat intake linked to common bowel condition diverticulitis: “Those who are higher quantities of red meat tended to use common anti-inflammatory drugs and painkillers more often; they smoked more, and they were less likely to exercise vigorously. Their fiber intake was also lower” (12).

- Study: Meat intake and mortality: “Subjects who consumed more red meat tended to be married, more likely to be a current smoker, have a higher body mass index, and a higher daily intake of energy, total fat and saturated fat, whereas they tended to have a lower education level, and were less physically active” (13).

In other words, red meat eaters are physically unhealthier and more frequently engage in unhealthy habits.

Given this, how can we pinpoint that red meat is the problem?

Again, the answer is similar; we cannot.

This fact does not mean that we should ignore epidemiology, it just says that correlation is not proof of causation.

Key Point: Epidemiology cannot prove that red meat is harmful. There is a correlation, but there are many confounders too.

Pros and Cons of Randomized, Controlled Trials

Since epidemiology has limitations, some people prefer to look at randomized, controlled trials (RCTs).

These are often called “the gold standard” of science because they can show what effect something has on people in a controlled environment.

For example, a randomized trial on red meat in human subjects can show if eating that meat affects the health markers associated with cardiovascular risk (like blood-glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure readings).

Therefore, randomized, controlled trials can show evidence of (or lack of) harm.

However, RCTs are not always perfect, and they also have some limitations.

A Limitation of RCTs

Some researchers argue that however useful RCTs might be, they cannot accurately predict long-term outcomes.

One of the reasons for this is that chronic diseases often have a long-latency period and take decades to develop.

Concerning health markers, the results over a 4-week period may not be the same as the findings over a 4-year period.

Again, they could be the same, but we do not know.

Overall, both observational studies and randomized trials have positives and negatives.

For these reasons, if the results of randomized controlled trials confirm observational findings, it gives a strong indication that a theory is correct.

Key Point: RCTs have many strengths, but they are not perfect.

What Do Observational Studies Say About Red Meat?

Many epidemiological studies find associations between red meat and cancer or cardiovascular disease.

Here are findings from some large and recent studies;

- In a cohort study that followed 34,057 women for 13.2 years, consumption of processed red meat was associated with heart failure. However, unprocessed meat was not (14).

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of 60 studies found that red meat and processed meat consumption are both associated with colorectal cancer (15).

- In a study population of 74,645 Swedish people, high red meat consumption was associated with a higher risk of CVD and all-cause mortality (16).

- A dose-response meta-analysis featuring seventeen prospective cohort studies on red and processed meat consumption found associations between unprocessed red meat and mortality in US populations. However, there was no association in European and Asian populations (17).

- A review of the existing evidence determined that processed and unprocessed meat is not beneficial for cardiovascular health, and public health guidance should focus on reducing consumption (18).

Despite these observational findings, a recent systematic review found that there is no mechanistic link between red meat consumption and colorectal cancer.

Key Point: Epidemiology on red meat is not always consistent, but it generally shows associations between red meat and increased mortality.

What Do Randomized, Controlled Trials Say About Red Meat?

What happens when you eat “too much” red meat?

According to randomized trials, the answer to that question is “nothing bad.”

In contrast to the epidemiological findings, randomized, controlled trials find red meat consumption to be either neutral or beneficial to health.

Here are the findings of some recent randomized, controlled trials on red meat;

- In an investigator-blinded, randomized trial, 41 overweight individuals improved multiple markers of cardiovascular risk on a Mediterranean-style diet either with or without reductions in red meat intake. In other words; there was no difference between high and low red meat intake (19).

- In a systematic review of 24 randomized, controlled trials, the highest category of red meat consumption (> 3 servings of red meat per day) had no negative effect on blood lipids (cholesterol) or blood pressure. It also increased HDL levels, which is associated with reduced cardiovascular risk (20).

- In a randomized, controlled trial, tripling the red meat intake of toddlers aged between 12 and 20 months resulted in no changes to their cholesterol profile (21).

- A meta-analysis of 8 randomized controlled trials featuring 306 individuals found that there were no significant differences between beef, poultry, and fish in their effect on the lipid profile (22).

- In a population-based randomized, controlled trial in Thailand, there was no association between meat intake and a positive colorectal FIT test among 1,167 participants. The only variable associated with a positive test was being of an elderly age (23).

Key Point: Randomized, controlled trials do not show evidence of harm from red meat consumption.

Discrepancies and Thoughts To Ponder

As we can see, there are apparent discrepancies between the evidence from epidemiological studies and randomized trials.

Does this automatically mean we should discard the findings of observational studies?

No, it does not.

However, it does suggest that we should take them with a pinch of salt.

If red meat indeed was harmful, would we not have seen some evidence of this in a high-quality RCT?

Also, why do studies in Western countries almost consistently find associations between red meat and cancer when Asian observational studies do not?

Is it something about the diet/lifestyle?

Colorectal Cancer and Insulin

Regarding colon cancer, there are also various other things that have strong and consistent associations with risk.

One of these is high fasting insulin levels (hyperinsulinemia) and low HDL levels; in other words, metabolic syndrome.

A wealth of studies show that, more often than not, colon cancer sufferers tend to have high fasting insulin levels. (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29).

Key Point: There are large discrepancies between epidemiology and randomized, controlled trials.

Red Meat and High Heat Cooking

This could be a whole article on its own.

Some researchers believe that cooking meat on a high heat creates the formation of several damaging chemicals.

When amino acids and creatine found in meat are exposed to high temperatures, they react and form heterocyclic amines (HCAs), a carcinogen (30).

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are another toxic compound created by the high-heat smoking or cooking of meat on an open flame (31).

A wide variety of data links HCAs and PAHs to cancer (32, 33, 34, 35, 36).

How Can We Minimize Risk?

Here are several ways to minimize the intake/effect of HCAs and PAHs:

- Opt for less abrasive heating methods – such as boiling and stewing.

- The majority of HCAs are created at a temperature of 300˚F or above.

- Using polyphenol-rich marinades (think herbs and spices) shows an up to 88% reduction in the formation of HCAs (37).

- Frequently flipping the meat when grilling reduces burning and formation of HCAs/PAHs (38).

- Red wine – either in the meal or alongside it – significantly reduces damage from HCAs/PAHs (39, 40).

- Intake of green vegetables appears to be protective against damage from HCAs/PAHs (41, 42).

Key Point: Cooking meat at high temperatures may create carcinogens. However, it is possible to minimize the risk by cooking at sensible heats and using marinades.

Red Meat: How Much Is Too Much?

The amount of red meat considered as “too much” depends on whether we believe that caution is necessary.

If we believe that red meat is “harmful,” and we look solely at the epidemiological evidence, we should probably restrict our red meat intake. Similar to the UK NHS suggestions, based on those studies, around 500 grams of red meat per week would appear to be about right.

However, I am not convinced that red meat is “harmful”, and the evidence does not persuasively show this.

In fact, randomized, controlled trials demonstrate that red meat is either neutral or beneficial to our health.

Furthermore, with the impressive range of nutrients red meat provides, it is something that I think we should value in our diet.

Personally speaking, I do not think that red meat has to be carefully restricted. It is a nutrient-dense food that brings much nutritional value to our diet.

Final Thoughts

Overall, everyone will probably have a different take on the studies on red meat.

However, it is worth remembering that correlation does not equal causation.

Lastly, remember that media headlines are more about selling papers (or getting clicks) than accurately portraying a study.

Source: Article by Michael Joseph (https://www.nutritionadvance.com/how-much-red-meat/)